|

Television Experimenters.com

Mirror Screw History

The MIRROR SCREW

and its Place in Television History

|

A History of the Mirror Screw

To many people today, television "came out" just after the second World War. Some who are older may remember a time before WWII, when there was television with pictures that were much smaller than they are today. The most common cathode ray tubes then were 5 or 7

inches in diameter. Later after the war, 7, 10 and 12 inch sets became common and for those who had the funds, there were projection sets able to produce newspaper-sized images. All of these sets by then, were fully electronic/optical in nature.

However, long before this, television was on the scene in an experimental mechanical form. As early as 1928, there were regularly scheduled television programs being broadcast, by a number of AM broadcast transmitters on the East Coast and in the mid-west. Later there were also broadcasts originating from the West Coast as well. The Nipkow disk by this time had been known for more than 40 years and was almost exclusively used as the scanning device in all cameras and receivers at that time. In the meantime, Philo Farnsworth and Valdimir Zworykin in the US and Manfred Von Ardenne in Germany, had for the most part bypassed the mechanical systems and instead were hard at work, developing totally electronic systems. They and others

had started this work in the very early 1900's, but it was Philo Farnsworth who was the first in 1927, to patent and demonstrate a complete totally electronic system. |

In 1928, even the best available electronic televisions did not perform as well as the crudest Nipkow disk mechanical system. Furthermore, the mechanical receiver was a very simple, low cost device. So simple that thousands of xperimenters could and did build their own receivers, based on construction articles appearing in newspapers and magazines of the day. Experimenters found satisfaction in their technical success. However, the general public that had seen television, were making demands for technical and programmatic improvements that the engineers could not provide at the existing stage of television development.

The only mechanical scanners that showed promise for commercial success in 1928 were the mirror drum and the Nipkow disk or one of its derivatives, such as the lens disk. In that same year a new rotary mirrored device was patented, by D. B. Gardner of Los Angeles, which became known as a mirror screw. It offered a number of important advantages over all of the previous mechanical scanners.

|

|

A mirror screw consists of a number of similar thin aluminum or stainless steel plates mounted one above the other, each with a

mirrored surface on one of its long edges. These plates are attached at their center on an axle and clamped into a spiral staircase located at similar angles. Each mirror provides

just one image line in the final image; therefore a 60-line image requires 60 mirrors, In use, the mirror screw requires a light

source in the form of a line, the width of which is the same as the mirror plate thickness and at least as long as the total height of the stack of mirrors in the screw. The plane of the axle and the line source must be the same.

The main advantage of the mirror screw over other scanning methods is that it will produce an image as large as itself. Compare this to the Nipkow disk where its image represents

only a very small portion of the area covered by the total disk surface. The mirror screw also provides very bright images over broad viewing angles, as it reflects a large portion of the light from the source on to the viewer. Another major advantage is that it produces the ideal scan line, where there is no overlap

nor is there any space between lines. This gives the image more brightness and the appearance of having more lines than are

actually present. However, the idea of the mirror screw did not catch on for a number of years. In spite of its excellence, very few

people outside of the European countries ever saw a mirror screw in operation, |

|

Engineer, Franz Von Okolicsanyi, wrote up and described a similar mirror screw, complete with drawings. However, he had apparently not patented his idea at the time. To this day, to many Europeans, Okolicsanyi is considered to be the inventor of the mirror screw.

TeKaDe, a company located in Nurnberg, Germany was one of the first to invest serious money and effort into television. They had been producing Nipkow disk type of receiving kits for both the German and English 30 line

broadcasts. Their television development program began in earnest in 1930, when they took over the development laboratory and patents ownership of Telehor AG, which had been founded by the famous Hungarian television specialist Dionys Von Mihaly. The ongoing development work was to continue with F. V. Okolicsanyi, installed as the new head of the development Laboratory. With him came the technology of his mirror screw. It was to serve as a replacement for the Nipkow disks and mirror drums, which were becoming ever more unwieldy with increasing image size, number of lines and frame rates. |

In late 1931, TeKaDe was continuing development work on both mirror screw and CRT equipped receivers. At a radio show in Berlin, TeKaDe put on a display of both a mirror screw and a cathode ray tube receiver. For the first time, other companies also presented their receivers with cathode ray tubes. The quality and brightness of the TeKaDe mirror screw pictures were surprisingly good and met with the approval of the experts. It was recorded that the mirror screw receiver provided a very good picture and that the receiver cabinet required the least amount of physical space, compared to the others. |

| |

In 1931, Tekade was continuing development work on both mirror screw and CRT equipped receivers. At a radio show in Berlin put on a display of both types of receivers. Their mirror

screw set was their model SS 7/90 receiver that produced a 90-line picture measuring approximately 2.8" by 3.2" inches , (7X8cm). This receiver was their first, able to also receive the accompanying sound on short wave. Shown here to the right, is a 30 line horizontal scanning mirror screw receiver of French origin. The larger of the two cabinets contains the mirror screw and its associated drive motor. The taller cabinet contains the

light source that illuminates the mirror screw. Not seen in this photo are the necessary amplifiers and power supplies. This photo is dated 1932 and this receiver might have been used to view signals originating in Germany or France. |

|

| |

In 1933, at the Berlin show again, cathode ray tubes, mirror drums and TeKaDe mirror screws were all about equally represented. TeKaDe was showing two improved 180-line mirror screw receivers, one with a 5.4" by 6" (13.5X15cm) picture and another measuring 10.7" by 12" inches, (27X30cm). Both receivers were equipped with their new Kerr cell, using zinc crystaline material instead of nitrobenzene. The resultant images were exceptionally bright, surpassing the brightness of all of the cathode ray tubes, including the one in TeKaDe's own electronic receiver.

In 1934, TeKaDe was the only company manufacturing and developing both mechanical and electronic television at the same time. It was in this year that all of Germany's 180-line broadcasts included their accompanying sound transmissions. This represented the considerable progress of German television technology, when one considers that at that same time, the BBC was still transmitting the Baird 30-lines/12.5 frames format and Rome was at 60-lines/20 frames. There was a clear-cut tendency in television technology, in the direction of larger images and a larger number of lines.

|

|

TeKaDe was forced time and again to consider how much the number of lines could be increased in their mechanical receivers with mirror screws. For larger pictures, they considered using a smaller mirror screw in a projection type of receiver. At this time they were confident that they could go to 240 lines, should it be necessary. Although TeKaDe believed that the mirror screw was

superior to the cathode ray tube, this did not hinder TeKaDe's laboratory from continuing to intensively study the cathode ray tube as it applied to television receivers. There were actually moments when they seriously considered stopping work on cathode ray tube receivers and transfer those efforts and funds to the ongoing mirror screw development work.In 1935, Germany continued with 180-line transmissions, but added interlacing to increase the frame rate from 25 to 50. TeKaDe was able to make a minor modification to their mirror screw itself and with this change, image flicker completely

disappeared at the higher 50 Hz frame rate.

In 1937, German technology took a major step forward. Their transmissions jumped from 180 lines to 441 lines. With this increase, all existing mechanical scanning devices were finally eliminated. There would be no more mirror screw scanners from TeKaDe. In the years following, TeKaDe concentrated on

electronic television. |

The mirror screw was a major improvement over previous scanning methods. The number of mirrors ranged from 30 to 180 and it found its greatest usage in Germany. The advantages of the mirror screw were its light very wide viewing angle. They were also very easy to use, many times simply mounted on the end of the driving motor shaft. A typical mirror screw might be approximately 6 inches high and 7 inches wide. As mentioned earlier, some of the 180 line mirror screws manufactured in Germany measured about 10" by 12". For a Nipkow disk to show a 180 line,10" by 12" picture, it would have to be over 53 feet in diameter. On the other hand, a 12" Nipkow disk would produce a 180 line picture less than 1/4" square.

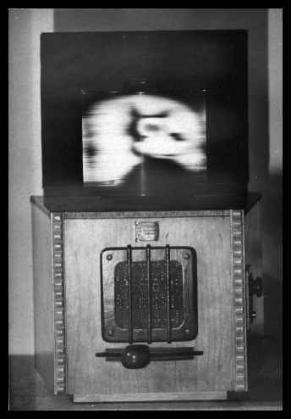

The photo here above, shows a receiver patterned after a German model, using a 7 inch diameter TeKaDe, 120 line stainless steel mirror screw. The image of Felix the Cat was generated by a 120 line Nipkow disk camera, coupled to the receiver by way of a coaxial cable. This receiver was built and demonstrated before 200+ members of the Antique Wireless Association (AWA), in 1998 by Peter Yanczer. The picture was bright and the field of view on the mirror screw is very wide. People located in an arc of some 120 degrees were able to see the image simultaneously.

The mirror screw was favored as a scanning device by only the one major television company, TeKaDe in Germany. Most likely this was because the head of their development laboratory considered himself to be the inventor. It was first shown, configured for 30-lines and some 6 years later, after many improvements, reconfigured for 180-lines. It was then declared obsolete, although it could have done a bit more. In all the years that it was in use, it was always superior to all other scanning devices, providing larger, brighter pictures, greater apparent resolution, a small package versus picture size and a potential low manufacturing cost. The

obvious question is why was TeKaDe the only company to use the mirror screw. Certainly, part of the answer is that the competitors most likely felt that their electronic receivers were being improved at a rapid rate and potentially would be better suited to operate at the higher line rates that were most definitely coming in the future. Of course, TeKaDe was very wise in continuing their electronic receiver development work for the same reason, because the cathode ray tube was the only scanning device that could make that jump to 441 lines and beyond. |

Page 2

All rights reserved. |

|